maritime communications

radio communications

radio history

titanic

wireless operator

CQD signal, early radio technology, Guglielmo Marconi, Harold Bride, history of wireless communication, iceberg warning, Jack Phillips, marconi, maritime communication, maritime safety, Radio Act 1912, radio distress call, radio history, RMS Carpathia, RMS Titanic, shipwreck, SOLAS, SOS signal, SS Californian, Titanic, Titanic communication failure, titanic disaster, Titanic iceberg collision, Titanic wireless operators, wireless telegraphy

9M2PJU

0 Comments

How Wireless Telegraphy Shaped the Titanic Tragedy

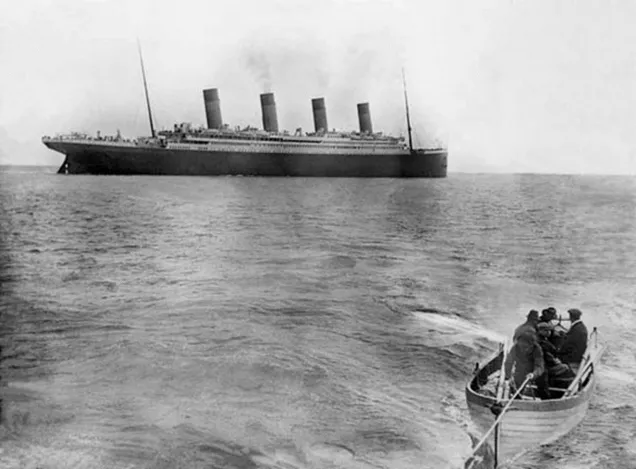

On the cold night of April 14, 1912, the RMS Titanic collided with an iceberg in the North Atlantic. By the early hours of April 15, the “unsinkable” ship had vanished beneath the waves, claiming more than 1,500 lives. It was one of the most devastating maritime disasters in modern history. But in the midst of this tragedy, a powerful new technology emerged as both a symbol of hope and a tool of profound change—wireless telegraphy.

A Revolutionary Technology Aboard the Titanic

At the dawn of the 20th century, wireless telegraphy was nothing short of revolutionary. The idea of sending messages through the air without wires, over vast distances, had only recently been realized by Guglielmo Marconi, the Italian inventor widely credited with making radio communication a practical reality.

By 1912, Marconi’s technology was making waves—literally and figuratively—in the maritime world. The Titanic, the most advanced passenger ship of its time, was equipped with a powerful Marconi wireless set. It could transmit messages up to 500 miles by day and over 2,000 miles at night under favorable conditions. This system was not operated by the ship’s crew but by two Marconi Company employees: Jack Phillips, the chief operator, and Harold Bride, his assistant.

Their job wasn’t just to handle navigational warnings; they were also responsible for sending personal messages from wealthy passengers—much like telegrams, but over the air.

A Flood of Warnings, But Not Enough Action

In the hours before the Titanic struck the iceberg, several ships in the vicinity sent wireless messages warning of ice fields directly in the Titanic’s path. These warnings were received by Phillips and Bride, but due to the sheer volume of passenger messages, many of the ice warnings were never relayed to the bridge or were not treated with urgency.

At around 9:40 p.m., the Mesaba sent a detailed message describing heavy ice directly ahead. However, Phillips, overwhelmed with traffic, never passed it on. More critically, the SS Californian—a ship only about 10 miles away—sent a direct warning that was brusquely rebuffed. Phillips, likely irritated by the interruption, told the Californian’s sole wireless operator to “shut up” as he continued to send personal messages for passengers.

Shortly thereafter, the Californian’s operator powered down for the night, unaware that Titanic was mere minutes from catastrophe.

Distress Calls in the Dark

At 11:40 p.m., the Titanic struck an iceberg. The ship shuddered, and water began to flood the lower compartments. Wireless operator Jack Phillips continued working amidst growing chaos. By 12:20 a.m., he began transmitting the distress call “CQD,” the traditional maritime signal for help. At the urging of Harold Bride, he also sent the new international distress signal “SOS,” which had been recently introduced and was gaining adoption.

“Send SOS—it’s the new call, and it may be your last chance to send it,” Bride reportedly told Phillips.

These distress calls were picked up by several ships, most notably the RMS Carpathia, which immediately turned around and steamed toward the Titanic at full speed. Unfortunately, it was over 50 miles away and would not arrive in time to prevent the loss of life.

The Californian, much closer, remained silent—its operator asleep, its bridge unaware of the tragedy unfolding so near.

A Life-Saving Technology, Yet Still in Its Infancy

While wireless communication could not prevent the Titanic’s sinking, it was instrumental in saving over 700 lives. Without it, the Carpathia would not have known of the disaster until it was far too late. Survivors in lifeboats may have drifted for days before rescue.

Yet the tragedy also revealed critical flaws: the dependence on just one or two operators, limited equipment hours, and the prioritization of commercial traffic over safety messages. These shortcomings fueled public outcry and political pressure.

The Titanic’s Legacy: Regulatory Reform and 24-Hour Radio Watches

In the wake of the disaster, the world realized that maritime communication needed a radical overhaul. In the United States, Congress passed the Radio Act of 1912, which required ships to maintain a 24-hour wireless watch and regulated the use of radio frequencies to avoid signal interference.

Internationally, the tragedy led to the first International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS) in 1914, which set standards for lifeboats, emergency procedures, and radio communication that still influence maritime law today.

It also solidified Marconi’s place in history. Although he was not aboard the Titanic—he had taken the Lusitania a few days earlier—his invention had proven its worth under the most tragic of circumstances.

Reflections from the Wreckage

Today, the story of the Titanic is told not just as a tale of human hubris or engineering overconfidence, but also as a turning point in technological history. The ship’s loss catalyzed reforms that made seafaring safer. It showed the world that wireless technology wasn’t just a novelty—it was a necessity.

In an era where we now carry satellite communication in our pockets and track ships in real time, it’s easy to forget that it all began with sparks across the Atlantic, a distress call in the dark, and a man named Marconi who dared to imagine that messages could fly through the air.

Post Comment